Maackia 022: On contrast

I’m Nathan Langley and this is Maackia, a monthly newsletter on working with contrast!

A sprinkle of joy in a tragedy; the bubbling conflict in a comedy; a moment of reflection in an action movie. Each one enhances the other.

What temperature is a bucket of water in a sauna? Easy! Stick a thermometer into the water and you will find out instantly. Done. Settled.

When I started to sit in a proper sauna and experienced what that meant, I discovered something strange. Haunting, really (clearly, as it is still on my mind over ten years later). The water in the bucket changed temperature.

I don’t mean it gradually increased in temperature as time went by, either. When I was first in the room, I wet my face cloth in the bucket of water. It was frigid. Of course it was — the water was directly from the lake and it was May! The ice covering the water through winter was still a recent memory.

But after filling the room with steam and jumping into the lake to seek relief from the unbearable heat, something unexpected happened. When I returned to the sauna, the water in the bucket felt hot.

Barely 10 minutes had passed from my initial encounter with the bucket of water to when I sought the warmth of the sauna again after jumping in the lake.

Clearly, I must have a future as a magician!

Michael: So… this is the magic trick, huh?

Gob: Illusion, Michael. A “trick” is something a whore does for money. (Michael points out that a bunch of kids are staring at Gob with their mouths open) …or candy!

— Arrested Development s1e01

But in all seriousness, it wasn’t the bucket of water that changed. I did. My context changed as I made my way through the sauna ritual.

I find talking about colour in gardening is often fraught with difficulty. What you see is different from what I see, just as the water’s temperature in the bucket will feel different to you and me even though it is a single, measurable temperature.

In town, I typically encounter traditional mixed perennial plantings with the odd tree or shrub thrown in. When I read books and browse social media, I encounter the opposite, as Piet Oudolf’s influence has slowly changed the perception of naturalized plantings. Less is no longer more. In fact, the argument now is that you need lots and lots and lots of different textures, colours, and species to hold people’s attention throughout the year. “Simple” gardens are last year’s fashion and, oh, so, boring.

But I can’t help feeling like that is a dangerous course of action. At least, for people looking after their gardens at home.

I decided to experiment a bit with one of the designs I have been working on this winter. I wanted to deliberately play with contrast in three ways:

(1) shifting between large areas planted heavily with flowering perennials and a few tall grasses mixed in (block planting) vs. areas predominantly planted with grasses and a few flowering perennials mixed in (matrix planting)

(2) sticking with analogous colours or tones for most of the flowering perennials, while adding one species that contrasts heavily at a given time

(3) keeping the flower types to two or three kinds, while adding one type that is entirely different

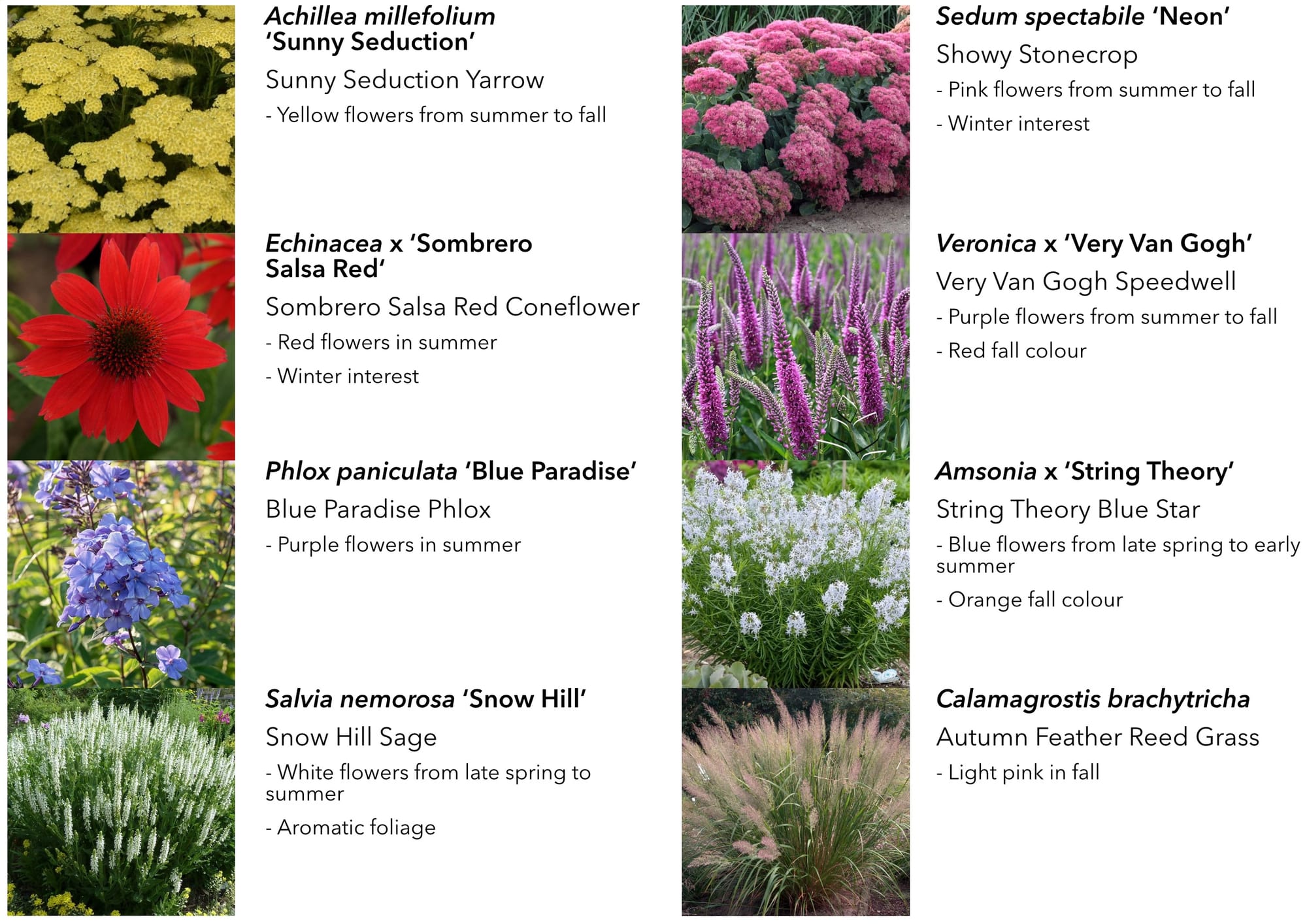

The picture above is an example of one of the flowering perennial sections from the design and shows the plants I used. It’s not particularly earth-shattering at first glance. You can see that the colours are mostly the same, with one contrasting colour (blues vs red in the spring and early summer; pinks vs yellow in late summer and fall).

The flower types are also grouped similarly. There are only two species within each type (flat-topped, spiked, and branched) except for the Echinacea and the Calamagrostis that act as contrasts. I even tried to keep the pattern the same during the seasons (ex: Achillea + Sedum vs Veronica in the fall).

What we are left with is a garden that presents varying levels of complexity depending on a viewer's knowledge and curiosity. But more importantly, it will (hopefully) be a garden that magnifies the textures, colours, and flower types that are used less frequently. This way I can keep the number of species lower than what is expected with today’s garden “trends” without sacrificing on the initial impact, appeal, and enjoyment of the garden through the seasons.

Why did I do this experiment? Because I feel this could be a better way forward than hopping on the naturalized aesthetic bandwagon. Having a more natural-looking garden is great! It is certainly far better than what I see most of the time when I am out exploring in Sudbury. But they aren’t really natural, and they require a lot of hard work and knowledge to maintain (if you can source the plants to build the garden in the first place).

I believe a simpler looking garden can be understood and enjoyed even if you don’t know the plants used or can see the difference between species like Phlox and Amsonia. I know the intended audience will enjoy it, especially with the other connected gardens that are thoroughly different. And, more importantly, it can be easily maintained into the future.

While we may not agree on what temperature the water is, or whether a particular flower colour is purple, we can all enjoy the beauty of the garden when it is put together. And we can rest easy knowing that the space enhances the positive energy in our lives, despite the work and attention it requires.

Even if what we feel is slightly different from each other.

n